Peter Bargen was just seven years old when he and his family narrowly escaped the Russian Gulag and almost certain death. The extended family members who remained in the former USSR were not so fortunate. Peter’s ethnic heritage is Mennonite. He grew up in a peaceful village in present-day Ukraine, as did many other Mennonites who immigrated to south Russia in 1763 at the invitation of Catherine the Great.

The paradise they lived in came to an abrupt end following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Millions of people perished during Joseph Stalin’s regime (1929-1953), among them thousands of Mennonites. They died from their enforced exile, persecution, famine and disease.

Now, in a story that crosses continents and binds together generations, the discovery of a large cache of rare and long-forgotten letters, written by Mennonites who were caught behind the Iron Curtain, many of whom were arrested and imprisoned, reveals the terrifying details of the fate of many families.

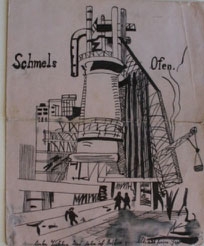

The letters (463 in the entire corpus) were sent to the tiny town of Carlyle, Saskatchewan, many of them smuggled through a subversive network of mail delivery. Peter Bargen’s parents stored the letters in a Campbell Soup box for almost 60 years. Shortly after their discovery, Peter and his wife Anne began the arduous task of translating and compiling the 463 letters. The earliest letters in 1930 tell of the arrest of an entire family (children aged 2 – 18 years). Little Lena, who is only eight years old, writes a letter to her aunt in Canada (Peter’s mother). Lena’s twelve year old sister sketches the smelter where she works (see below). In her letter she writes, “If you would see me in my torn dress you would be embarrassed to call me cousin.”

The flimsy cardboard box of letters that once contained soup cans captivated Peter and Anne Bargen. For three years, they worked at their kitchen table, reading, translating and crying at the fate of their family. They were uniquely qualified for the translation task; both were of Russian Mennonite descent. They could also understand many of the Russian expressions and read the German Gothic script. The enormous task of translating continued so that “this could be preserved for you, our children and grandchildren, as well as for others.” As Peter explains, “Unless something has been written, only fragments would be remembered and our past would become a misty dream shot through by only a few rays of light.”

The first 131 letters are from Peter’s uncle, aunt and six cousins (aged 2-18) who were sent to a prison camp in the Ural Mountains. These letters appear in the book Remember Us: Letters from Stalin’s Gulag (1930-37), and in the documentary film, Through the Red Gate.

Additional research and publications on the remaining letters in the corpus are forthcoming.

One of the letters includes a sketch of the smelter in the Ural Mountains where 12 year-old Tina Regehr worked (dated March 8, 1932).